When looking at a painting, I heard someone say:

“I could do that!”

Few statements have annoyed me more. It was laced with ignorance and, frankly, a hefty dose of arrogance.

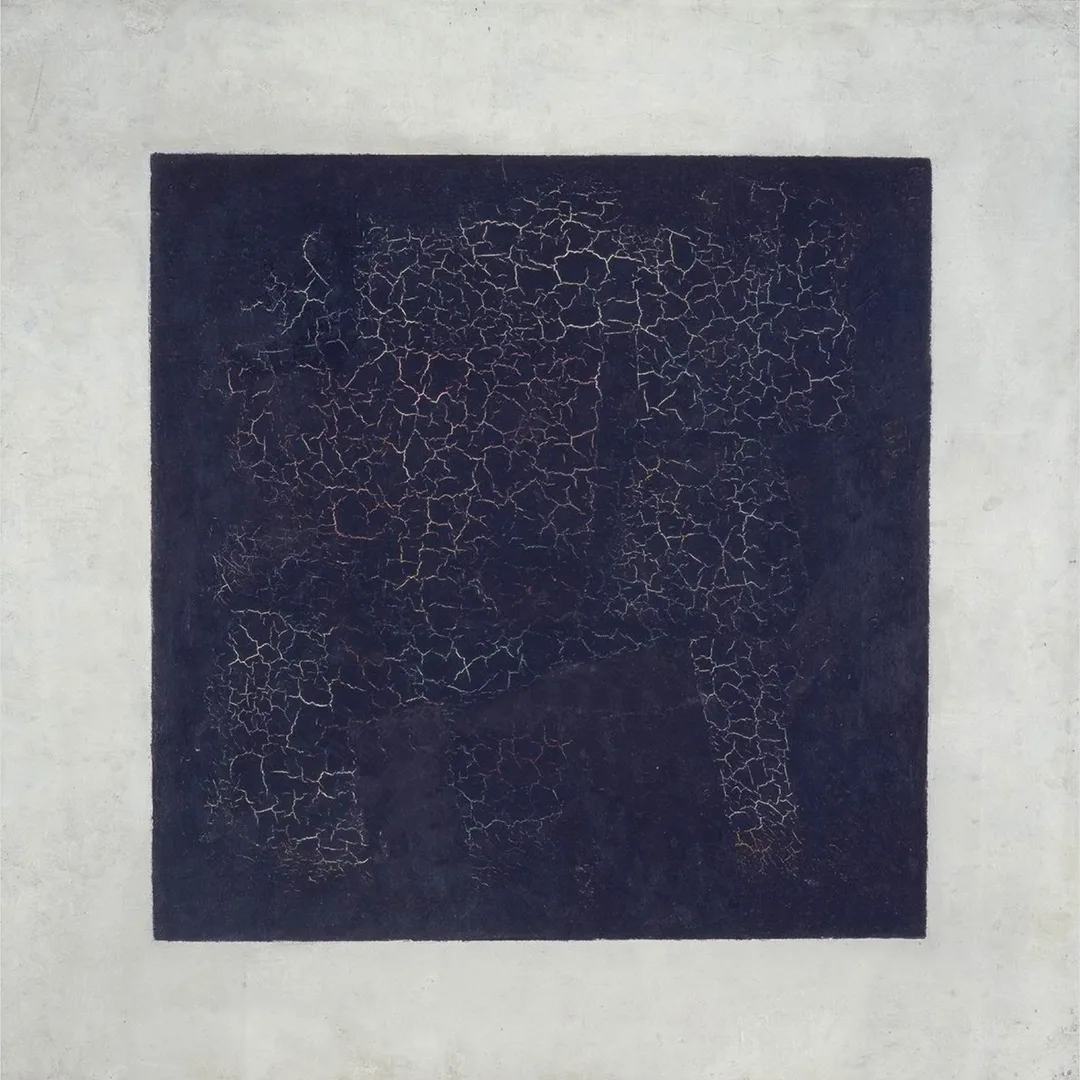

The painting in question was Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist Composition (1916), created during the devastation of the First World War. Russia, like much of the world, was reeling from catastrophic losses, food shortages, political turmoil, and unrest. To dismiss the work with such a casual remark is to overlook its meaning and the context of its creation.

Sold by the Nahmad family for $85.8 million at a Christie’s auction to a private collector

Malevich himself was no stranger to hardship. Born in 1879 in the Russian Empire to a Polish family, he grew up in modest circumstances. His father, Severyn Malevich, worked as a manager in sugar beet refineries, which meant the family moved frequently between small towns in Ukraine. This constant relocation gave Malevich an early sense of displacement. As one of fourteen children, he also knew the grief of losing siblings young, and later his father in 1904. These experiences of fragility, instability, and loss deeply shaped his artistic outlook.

Although he lacked a formal education, Malevich taught himself to draw by sketching the rural landscapes around him. After his father’s death, he attended the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, where he encountered avant-garde groups and absorbed the experimental energies of Futurism and Cubism. But Malevich sought to push further still.

In 1915, he unveiled Black Square, which declared the birth of Suprematism. This radical movement focused on pure geometric forms, offering order amidst the chaos of a collapsing world. Far from being “just a square”, the work was a profound statement: out of the darkness, a new beginning might emerge, held in the embrace of surrounding white space.

Original work is displayed at the State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Suprematist Composition built on this idea. It was not simply shapes painted on a canvas, but a reflection of Malevich’s lived experience, his emotional response to the world around him, and his belief in the possibility of renewal. To say “I could do that!” is to miss the point entirely. You might copy the shapes, but not the historical context, not the intent, not the vulnerability behind the work. These paintings carry an emotional weight that cannot be replicated.

Malevich is far from unique. Art history is filled with creators who poured their struggles and hopes into their work: Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch, Mark Rothko, Georgia O’Keeffe, Louise Bourgeois, Yayoi Kusama, Frida Kahlo, Henri Matisse, Jackson Pollock, Salvador Dalí, Jean-Michel Basquiat, each shaped by mental health battles, physical illness, loss, addiction, or personal upheaval. Their art is not decoration, but testimony.

To the person who dismissed Malevich’s painting, and anyone tempted to do the same, I would say this: take a moment. Consider what lies behind the canvas before you diminish someone’s creativity. Artists reveal their vulnerabilities through their work and invite us, the audience, into that space. The very least we can do is approach it with respect.