Over the years, I’ve learned that behind every body of work lies an imprint of the artist who conceived it. Their stories, experiences, thoughts, and feelings shape what we see on the canvas. Having studied Salvador Dalí, Frida Kahlo, Piet Mondrian, and Jean-Michel Basquiat, I felt it only fitting to choose Andy Warhol as my next lesson because of the close relationship between him and Basquiat.

Looking at old photographs that appear on my Instagram feed, I was intrigued by Warhol’s demeanour. I couldn’t help but wonder: what was going through his mind when he was socialising with the elite? He seemed to look inwards rather than outwards. He seemed awkward, yet comfortable. He appeared fully present in his surroundings, yet somehow separate, lonely. I felt there was a story of suffering amidst the pop and pomp of the art and celebrity world, a story I needed to delve deeper into.

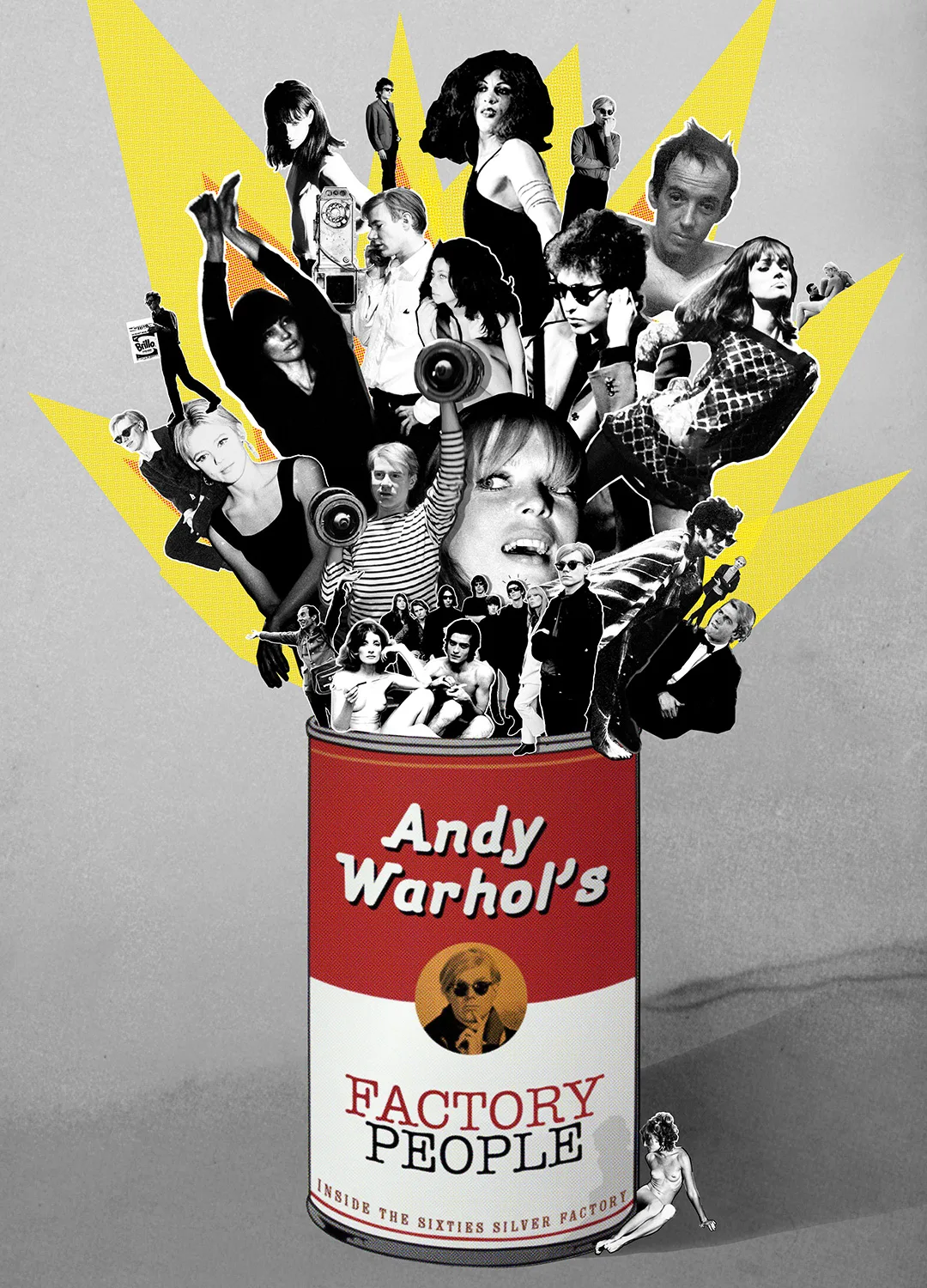

It has been just under a year since I began my research. I read various publications on Warhol alongside The Andy Warhol Diaries, and then watched the documentary on Netflix, and oh my days, that must be the best artist documentary I’ve ever seen. It was raw, unfiltered, and full of emotion. Learning about Warhol’s life from those who were at his side was incredibly moving.

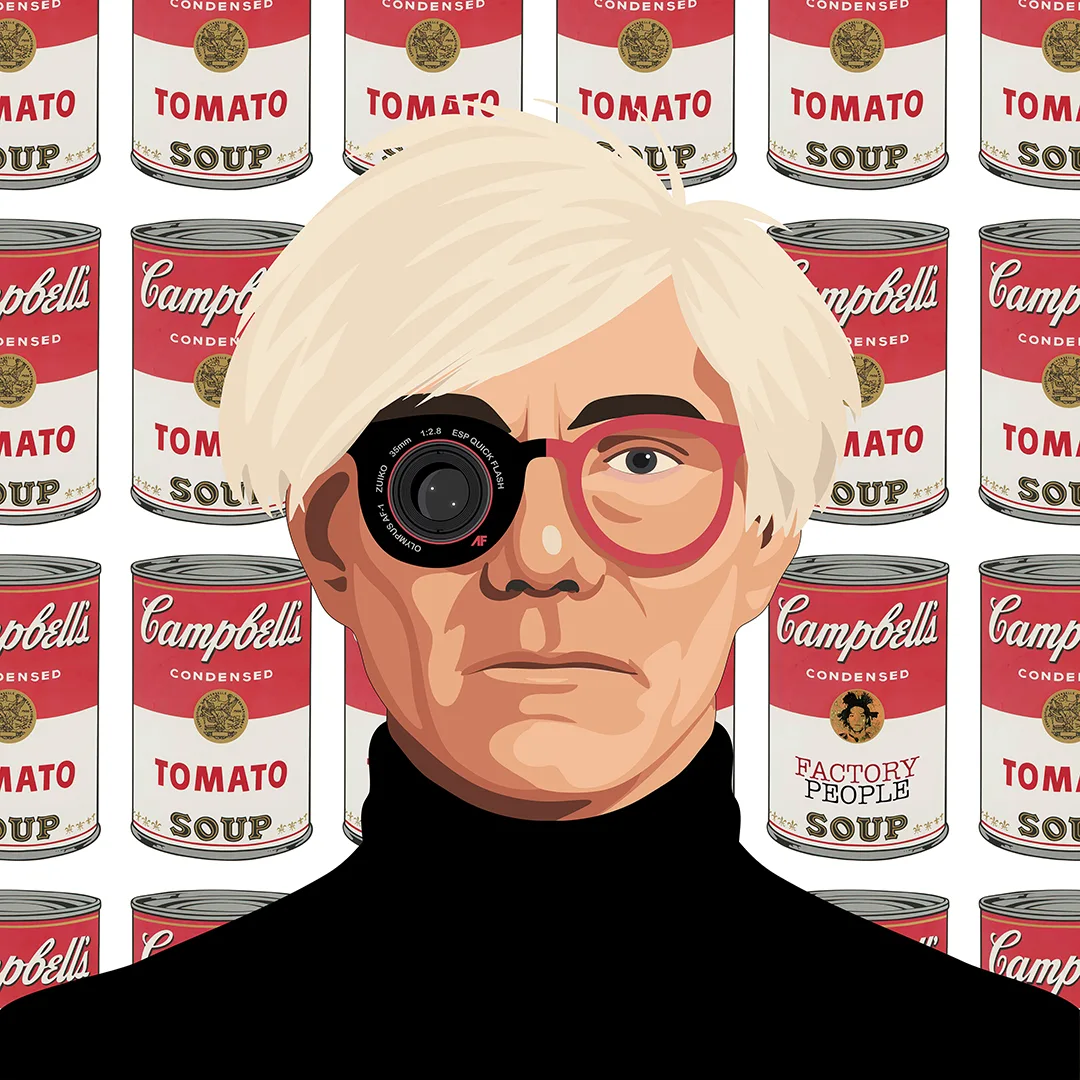

These explorations have stayed with me. I decided to create a more personal homage portrait rather than of his work this time, and although I have finished my final piece, I find myself not quite ready to let him go.

Why?

Because I found there’s a little bit of Andy Warhol in me.

Like myself, Warhol was a realist. Beyond his commercial pop art known for its nuance and its celebration of the seductive and glamorous lives of beautiful, famous people, there exists an oeuvre far darker, carrying a brutally honest portrayal of death and suffering. At a particularly low point in his life, Warhol once said:

“Really… what is life about? You get sick and die… that’s it. So, you’ve just got to keep busy.”

I’ve spoken those same words at times, except instead of saying “keep busy”, I say “keep going”. I could relate to the Andy Warhol I was sitting with in my living room. From the death of close loved ones, to health issues (including the gallbladder), to that feeling of ‘where do I fit in?’ as a child of immigrants who moved from their birth countries in search of a better life, and the deep yearning (in my case) to be the pretty English white girl with blonde hair and blue eyes.

He may have been a pop icon, a celebrity in his own right, but he was, just like me, a deeply layered human being, always finding ways to articulate his authentic self, to be better, to be kind and humble, and to remain relevant.

In creating this portrait, I aimed to layer Andy Warhol’s character alongside elements of my own life, forming a dialogue between his identity and mine.

Background

Why Campbell’s Tomato Soup?

Warhol: Growing up, Warhol and his brother often ate cheese sandwiches and tomato soup. The soup remained a staple throughout much of his adult life. As a result, this motif became one of his most iconic symbols, merging the personal with the commercial.

Me: Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans were installed around the columns of the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh during a 2007 exhibition. Seeing those cans all those years ago marked one of my earliest encounters with contemporary art in a public space.

Why 24 cans?

Warhol: He often worked in series, experimenting with repetition and scale. Many of his Flowers canvases were produced in 24 and 48 inch square formats.

Me: The number 24 holds personal significance as it was the number of my first flat after leaving my childhood home, symbolising new beginnings.

Why Basquiat?

Warhol: Jean-Michel Basquiat shared a close, complex relationship and artistic partnership with Warhol. Their collaborations reflected a mutual respect and creative tension.

Me: In the portrait, Basquiat appears on Warhol’s right side, just as he did in his own portrait of the two of them the first time they met. This is a subtle nod to my own life, as I always walk on the right side of my partner, Sunil. I added this detail to reflect loyalty and connection in both relationships.

What does Factory People mean?

Warhol: The Factory was more than a studio, it was a space of community, collaboration, and creative experimentation. Here, Warhol gave people the freedom to be who or what they wanted to be, without judgement, something he himself always feared.

Factory People was, in fact, a documentary series about the creatives who were part of Andy Warhol’s Factory in the 1960s. They worked with him on his art, films, and various other creative projects. I included the idea of placing it on one of the soup cans as a nod to the documentary’s poster.

Me: I’ve always dreamed of opening a creative studio where artists can exhibit, create, and share ideas freely. My fondest memories from high school are of the art department, days spent discussing ideas, followed by quiet hours of focused creation. That balance between collaboration and solitude is something I really miss, as I work alone most of the time.

Middleground

Warhol: The 1980s Warhol persona was polished, public, and self-aware. He often wore black (his favourite colour) turtlenecks with various pairs of glasses. I chose the red-framed glasses he wore at the Alasia Fashion Show in 1985.

Me: I, too, wore reddish NHS plastic-framed glasses growing up, an unintentional echo of Warhol’s iconic style, as I had no awareness of him at that age.

I was also born in the 1980s, further linking me to that era of his life.

Foreground

Warhol: In the 1980s, Warhol favoured the Olympus AF-1, a compact point-and-shoot camera released in 1986. Photography allowed him to capture the fleeting glamour and vulnerability of the people around him.

Me: My dad was a photographer, with a focus on portraits, and his passion inspired my own. I later took photography courses to develop that interest further. In my piece, I replace one of Warhol’s eyes with a camera lens, an idea inspired by the Edinburgh International Film Festival’s 2015 poster. This symbolises both mine and Warhol’s shared fascination with observation, creativity, and the delicate boundary between watching and being watched.

Andy Warhol looks directly at us, just as he did when he appeared in front of the camera in all the documentaries I watched. Like my previous portraits, where I sought to capture Frida’s beauty and Dalí’s uniqueness, I aimed for Warhol’s vulnerability by showing his stillness of expression. I’ve always been told I’m deadpan. Placid. Yet I know there is so much going on behind the exterior – as we now understand more deeply through The Andy Warhol Diaries.

Through the whole process, I discovered that our lives (though worlds apart) share a love for all creative mediums, the insecurities that come with age, and the fear of becoming irrelevant. And most poignantly, the quiet dread of losing those we love. At the centre of it all lies our health, fragile, unpredictable, and the true measure of how human we really are.

Yet within that fragility, creativity reminds us that we are still alive, still curious, still capable of beginning again. And this is where, despite his inner narrative, Andy Warhol thrived.